The funding mobilized for HIV over the past decades has saved millions of lives and strengthened the health systems of dozens of countries.

Free-of-charge antiretroviral medicines, HIV tests, condoms and other commodities—along with huge cadres of community health workers, enhanced health information and laboratory systems, strengthened procurement and supply chain management systems, and revived community health systems—are lasting legacies of the unprecedented global movement to fight HIV. Many of these resources are now playing important roles in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite their importance, however, pandemic response capacities have been under threat in recent years. The latest data show that the total resources available for HIV programmes in low- and middle-income countries have waned within the Sustainable Development Goals era, leaving HIV funding well short of the 2020 target set by the UN General Assembly in 2016. Financial resources from international sources for the HIV responses in these countries have declined by nearly 10% since 2015, with a 10% increase in bilateral funding from the United States Government—primarily through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)—offset by a 3% decline in funding from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) and a 31% decline in multilateral and bilateral contributions from other sources (see Chapter 2 for more details).

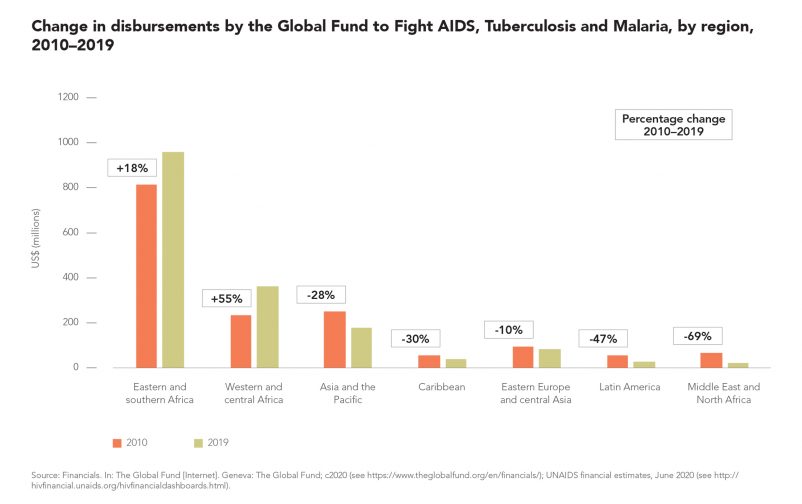

The destinations of United States Government bilateral funding and Global Fund resources for HIV have shifted since 2010. Annual Global Fund disbursements to eastern and southern Africa and western and central Africa increased by 18% and 55%, respectively, during 2010–2019, and they decreased in all other regions (Figure 5.15). The trend reflects Global Fund Board decisions to concentrate the organization’s support in regions with the largest burdens of disease and the least capacity to self-finance HIV programmes (270). Bilateral funding from the United States Government has similarly shifted to HIV responses in sub-Saharan Africa, including a US$ 1.3 billion increase in annual funding to countries in eastern and southern Africa and an increase of more than US$ 100 million in annual funding to countries in western and central Africa between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 5.16). United States Government bilateral funding for HIV responses in eastern Europe and central Asia also tripled during this period, from US$ 13 million annually to US$ 55 million annually.

The turmoil associated with the COVID-19 pandemic presents all countries with difficult resource allocation decisions. Efficiency gains will be emphasized as governments seek ways to meet rising demands with limited resources. Recent history suggests that the HIV response could be negatively affected by this decision-making.

In the past decade, international funding for HIV was significantly affected after the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, the 2012–2013 Eurozone debt crisis and the European Union reaction to the increased flows of migrants and refugees in 2014–2015. During these periods, the reductions in official development assistance for HIV were more pronounced than the decreases in official development assistance for health overall. While the trend in assistance for health broadly followed trends in total official development assistance as a percentage of government revenue in donor countries, assistance for HIV was hit hard. The effects were offset somewhat by the United States Government’s increased funding for HIV, but official development assistance from other donors decreased and has not yet recovered to pre-2014 levels.

In addition to a global health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and response is an economic shock of unprecedented scale. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank expect the global economy to contract by about 3% in 2020 (281, 282). By comparison, during the 2008–2010 financial crisis, global real GDP growth shrank by 0.1% in 2009 (compared with 2008). The International Labour Organization (ILO) has predicted that the pandemic could wipe out almost 7% percent of working hours globally by mid-2020, equal to 195 million full-time workers.

Government revenue is shrinking, just as additional investments are needed to protect people against the health, social and economic disruptions triggered by the pandemic. Low- and middleincome countries are especially at risk: many already are stricken with economic slowdowns, massive capital outflows and forbidding debt obligations. In sub-Saharan Africa, GDP growth is expected to slow from 2.4% in 2019 to well under -2% in 2020, marking the region’s first recession in 25 years. Countries dependent on commodity exports—including the region’s largest economies: Angola, Nigeria and South Africa—will be especially hard-hit.

High levels of debt exposure add to the vulnerability of countries. Indebtedness increased after the 2009 financial crisis as countries sought to bridge domestic investment savings gaps, encouraged by unusually low interest rates and exceptional levels of global liquidity. Due to sluggish global economic growth, however, commodity prices did not recover strongly enough to fuel the anticipated surges of economic growth across low- and middle-income countries. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 40% of low-income countries carried debt loads that were considered to be high-risk or in distress.

It’s highly likely that most low- and middleincome countries will need external resources, including concessional finance, to cope with the impact of the pandemic. In April 2020, the UN proposed a three-phased approach for providing debt relief. This would involve a debt moratorium, followed by targeted debt relief, and then measures to address structural issues in the international debt architecture and prevent defaults. The World Bank and IMF have called for a temporary suspension of debt repayments for the poorest countries, pending other actions to address financing and debt relief needs. Debt repayments of some low-income countries were suspended in April 2020, and G20 countries pledged to free US$ 20 billion in fiscal space for those countries to respond to COVID-19.

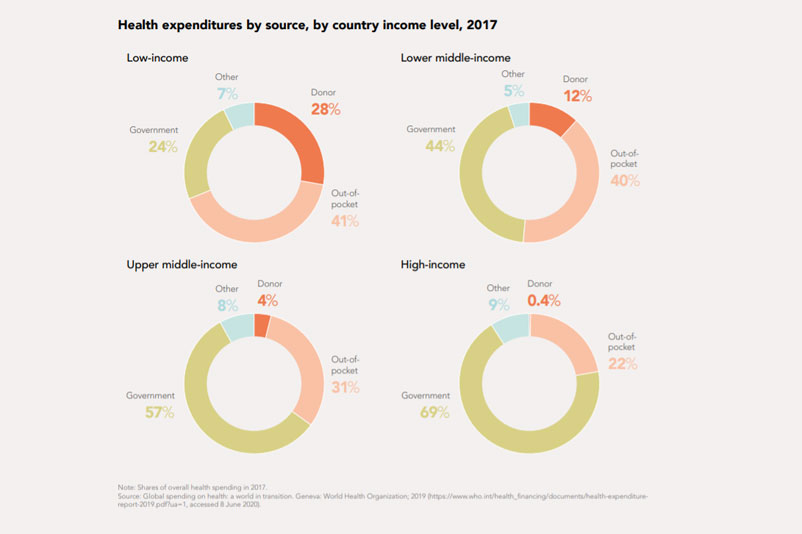

As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses, fiscal pressures might tempt a greater reliance on user fees and other forms of out-of-pocket payments to finance health care. Decades of evidence show that such recourse would be short-sighted and counterproductive.

According to the World Bank, people in low- and middle-income countries spend half a trillion US dollars annually—more than US$ 80 per person—out of their own pockets to access health services (288). Total out-of-pocket spending (including user fees) more than doubled in low- and middle-income countries from 2000 to 2017, reaching about 40% of total health spending (Figure 4.35) (273). It comprised even larger shares in some of the most populous low- and middle-income countries, such as India (>65%), Indonesia (>48%) and Pakistan (>66%) (289, 290).

Similarly, evidence from western and central Africa shows that user charges (in the form of so-called consultation fees or payments required for HIV tests, CD4 cell counts, and viral load or other laboratory tests) undermine uptake of nominally free antiretroviral therapy, hinder the retention of people in care and reduce the quality of care (due to opportunistic infections going undiagnosed) (297). Other studies in Botswana, Nigeria, Senegal and Uganda confirmed that user fees undermine adherence to HIV treatment (298–301).

The fees have similar effects on general health service use (302). Surveys in Burundi, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Mali and Sierra Leone found that fees deter people from using public health facilities, forcing many to delay care, seek alternative care in the unregulated private sector or experiment with self-treatment (303). User fees also are an inefficient financing mechanism for health services, with anticipated revenue increases and improvements in service quality typically minor or absent (292, 302, 304, 305).

User fees are a false economy. Large amounts of funding are invested in health programmes aimed at reaching all in need, such as global programmes for HIV testing and treatment, tuberculosis prevention and treatment, and maternal and child health. When user fees and other supplementary fees (such as consultation or attendance fees) are imposed at health facilities, those charges prevent the poor and most vulnerable from accessing or benefiting from those services, undermining the aims of those investments.